Things often don’t turn out as we expect them to, and they end up breaking unexpectedly—this is true for everyday life, as well as for software. We won’t deal with real life problems in this article, but we will tackle exceptions in code.

When code breaks, we say that an exception occurs. And when the program expects this to happen, it can “catch” the exception and react accordingly. For example, it can present the user with an error message, or it can retry the action that caused the exception.

A couple of months ago, we discussed exception handling in the context of SAP. In this article, we’ll discuss exception handling in Lua.

Exceptions in Lua code

In most modern programming languages, there’s a special block that can catch exceptions and handle them (like try-catch in C#). In Lua, it’s a bit different. In Lua, we need to encapsulate the code in a pcall function. The technical details are well explained in the Lua docs on error handling. It looks more complicated than it really is. Consider this example of error handling in LUA:

local success, result = trycatch(function()

--- Here is the actual code to be monitored

end)

if success then

-- Everything work as expected

else

-- The execution failed

peakboard.log(result.message)

peakboard.log(result.type)

endThe actual code is monitored, and the function returns two variables:

success, a boolean that tells us if there was an exception or not.result, an object that contains information about the exception, if there was one. It has the following attributes:message, the error message.type, the exception type. Apart from the type that happens in an SAP context, there are two possible types:LUA, which means the exception happened within the Lua code. For example, trying to access a non-existent element in a list.SYS:XXX, which is set when the exceptionXXXhappens somewhere in the runtime environment. For example, when we try to connect to a data server that doesn’t respond, it’s set toSYS:SqlException. By looking atXXX, we can even distinguish between different types or sources of runtime exceptions.

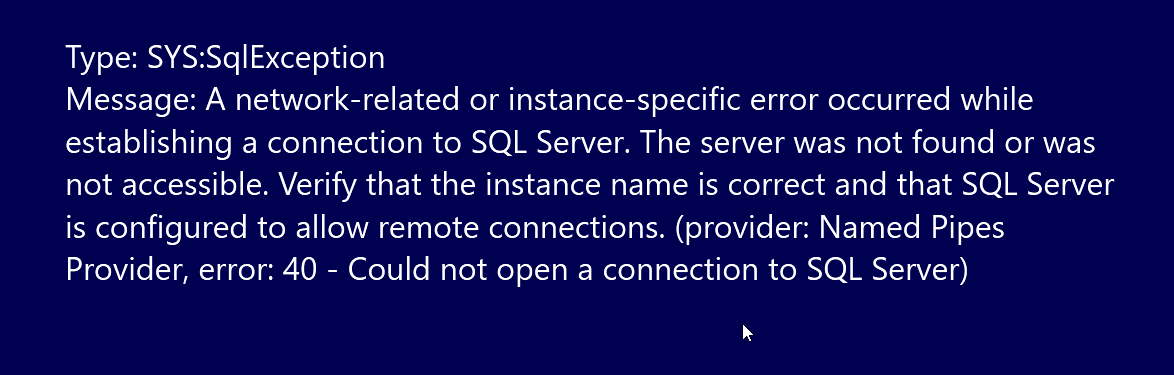

Here’s a real-world example of trying to connect to a non-existent SQL Server:

local success, result = trycatch(function()

local con = connections.getfromid("bwV8uGLHlHv9ZgAc5FtzmqRrspU=")

con.open()

con.executenonquery('INSERT INTO [Machines] ([MachineName]) VALUES (\'MyMachine\')')

con.close()

end)

if success then

screens['Screen1'].txtOutput.text = 'Everything is good!'

else

screens['Screen1'].txtOutput.text = 'Type: ' .. result.type .. '\nMessage: ' .. result.message

endAnd here’s the result in the final Peakboard app:

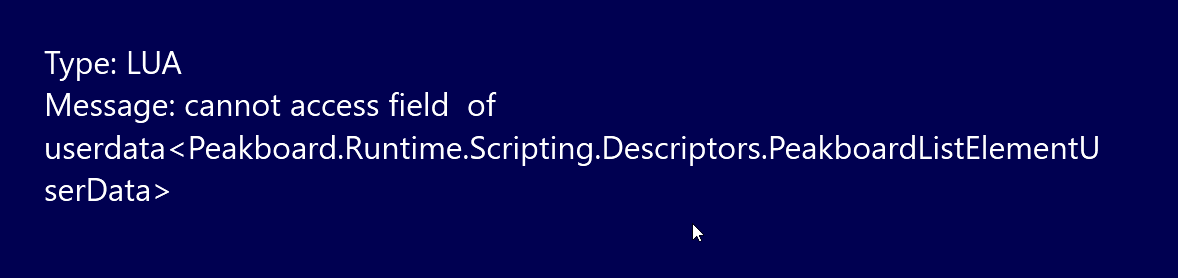

Let’s check out another example that generates a LUA and not a SYS exception by accessing a non-existent data artifact.

local success, result = trycatch(function()

local Dummy = ''

Dummy = data.MyEmptyList[5].Column_1

end)

if success then

screens['Screen1'].txtOutput.text = 'Everything is good!'

else

screens['Screen1'].txtOutput.text = 'Type: ' .. result.type .. '\nMessage: ' .. result.message

endAnd the result:

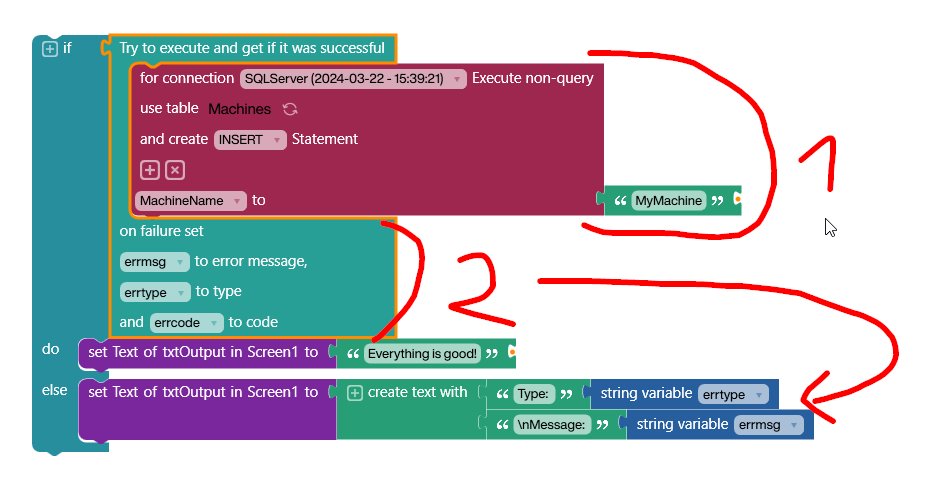

Try/catch in Building Blocks

The following screenshot shows the same example from earlier, but made with Building Blocks instead. The actual code is put into the try/catch frame (marked with 1). There are two branches—one for success and one for failure. There are also three generated variables that can be used in case of a failure (marked with 2). Error message and type is the same as the Lua example above. Code is only used in an SAP context.

Conclusion

Catching exceptions makes sense in a lot of contexts because it allows you to build apps that can react to unexpected events. With the built-in functions in Peakboard in both Building Blocks and pure Lua, it’s quite easy to wrap code in try/catch blocks and handle any errors that pop up.